Zhou Muzhi

Professor at Tokyo Keizai University

Editor’s note:

The ongoing discussions about Japan’s “Lost Decades,” a period of prolonged economic stagnation spanning 30 years, have sparked debates on whether Japan indeed lost momentum for three decades, the reasons behind it, and the potential takeaways for China. In June 2023, Professor Zhou Muzhi from Tokyo Keizai University delivered a lecture in Shanghai, offering a novel and comprehensive perspective on how Japan missed out on the prosperity driven by Moore’s Law. In the third part of his lecture, he analyzed the dangers brought about by Japan’s electoral system reforms.

1. Importance of macroscopic imagination

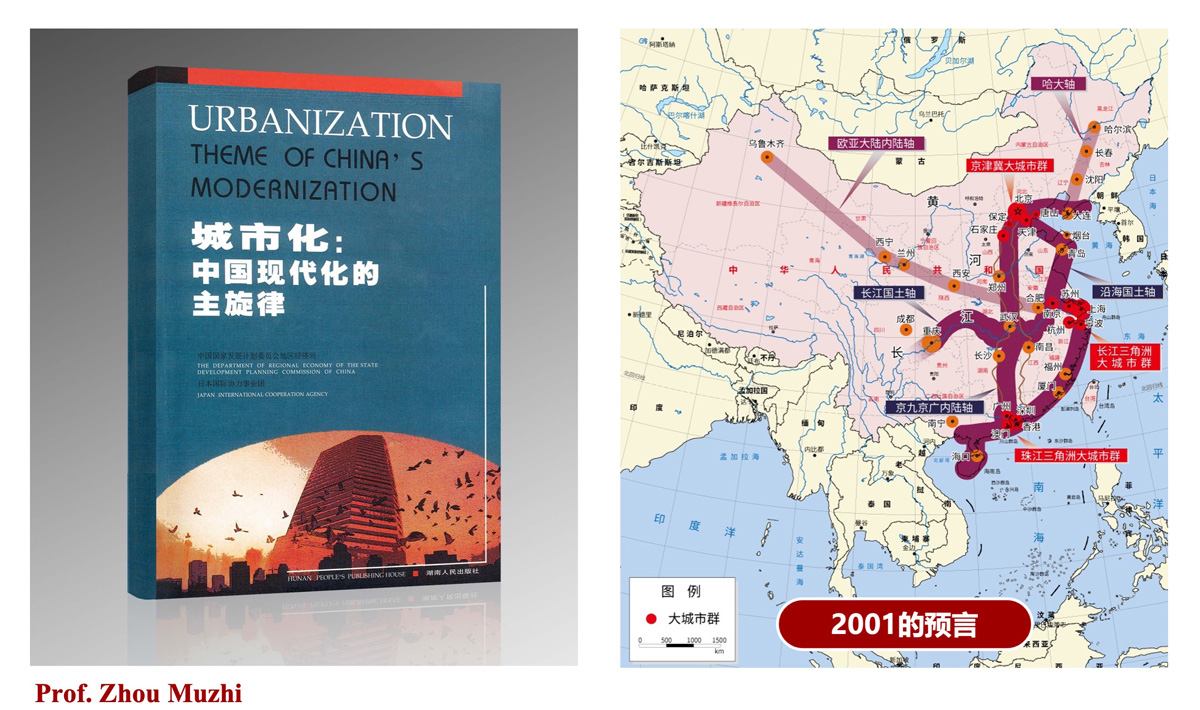

Twenty-two years ago, I made a prediction and also made a call to action, urging China to embrace urbanization, promote the development of large cities, and foster the growth of urban clusters. On Sept. 3, 2001, an international symposium titled “China Urbanization Forum – Strategies for the Development of Metropolitan Clusters” was jointly organized by the National Development and Reform Commission’s Regional Economic Development Department, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, China Daily, and the China Association of Mayors in Shanghai. This symposium was first held in Nanjing, then moved to Beijing, further to Shanghai, and finally to Guangzhou on Sept. 7. At the time, during the era of “small towns, big strategy,” discussing urbanization was considered a taboo. However, our series of conferences on the strategy for the development of metropolitan clusters gathered numerous renowned scholars and officials, including Yu Guangyuan, Ren Zhongyi, Chen Jinhua, Tao Siliang, Zhu Yinghuang, Lin Shusen, Li Ziliu, Yang Chaoguang, and Du Ping.

The media also provided strong support. On Sept. 3, China Daily dedicated an entire page to my opinion on metropolitan clusters. Economic Daily published my article titled “Embrace Small Towns and Large Urban Circles” on nearly an entire page. Following the symposium, People’s Daily published a full-page report under the title “Metropolitan Clusters: China’s Opportunities and Challenges,” offering comprehensive coverage of the event. Particularly in Guangdong province in southern China, local media showed extraordinary enthusiasm. Suddenly, media outlets nationwide began discussing two questions: What are metropolitan clusters? And why do we promote large urban clusters? This conference marked a beginning of discussions on urbanization, megalopolises, and metropolitan clusters.

This is how macroscopic imagination began and received enthusiastic responses. In fact, we collaborated with the National Development and Reform Commission to present this prediction and a series of policy recommendations based on years of research. In 2001, we foresaw that China would create the world’s largest new industrial agglomerations and metropolis clusters in the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, which would bolster China’s future.

The year 2001 was a watershed as two major events took place in the year: the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the ensuing U.S. launch of war in Afghanistan, as well as China’s accession to the WTO. Undoubtedly, these two events significantly accelerated the materialization of the prophecy of metropolis clusters, and today, this prophecy has become a reality.

Why were we able to accurately predict the future back then? The underlying logic is akin to Toffler’s prophecy — it’s the Moore’s Law. With an engineering background and years of research on industrial agglomeration, I firmly believed that the globalization of supply chains would swiftly take place. From this, I deduced that it would trigger a global industrial reshuffling, with China’s Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta being the wisest choices. The key to such large agglomerations is rapid urbanization and the growth of urban clusters.

To put it another way, Moore’s Law not only fosters microscopic imagination but also fuels macroscopic imagination. Macroscopic imagination often has the power to stimulate a nation’s developmental potential.

2. Japan once imagined big

During the aforementioned China Urbanization Forum, I invited many renowned Japanese scholars to participate in discussions. Among them were Tadao Kiyonari, president of Hosei University and a leading figure in Japan’s industrial policy; Shinyasu Hoshino, former vice minister of the Economic and Fiscal Policy Bureau and a key figure in Japan’s land planning; Shigeru Ito, a professor at Waseda University and head of Japan’s National Land Planning Review Council; Yuji Masuda, a professor at the University of Tokyo and a strategist in Japan’s information industry policy; Shuhei Konno, professor at Osaka Sangyo University and a land planning expert who led the Tokyo Bay Comprehensive Development Plan, among others. They are heavyweights in Japan’s land planning.

Japan’s National Comprehensive Development Plan stands out as the most important national plan in Japan. Experts and officials responsible for the plan, represented by the abovementioned individuals, have provided Japan with numerous grand imaginations. For example, high-speed railways have transformed the perception of time and the pace of life for in China. The idea of high-speed railways, known as the Shinkansen in Japan, was actually created by Japanese people. The concept of the Shinkansen was proposed in Japan’s land planning. As early as the 1960s, Japan introduced the concepts of informatization and high-speedization in land planning, using the Shinkansen and expressways to reorganize the country’s land utilization.

The coastal industrial zone is another significant concept advocated by Japan’s land planning. After World War II, Japan aimed to take advantage of global peace dividends and promoted the construction of new industrial bases in coastal areas, forming a Pacific industrial belt. By capitalizing on cheap global resources and a vast international market, Japan pursued large-scale imports and exports, resulting in its emergence as a major industrial exporter and achieving rapid growth.

Japan’s land planners not only put forth initiatives such as the “Doubling of National Income Plan” and the “Remodeling of the Japanese Archipelago,” but also introduced innovative spatial concepts like new industrial cities, watershed circles, and a one-day exchange circle in East Asia. It advocated for broad living areas, rural urbanization, and a multipolar decentralized land configuration as future land development ideas, laying the foundation for Japan’s post-war development.

From Japan’s land planning, it’s evident that Japan used to be a country that didn’t lack macroscopic imagination. However, why is it grossly lacking macroscopic imagination today? This is another toxin, an ailment bred by political reforms, wreaking havoc on the nation.

3. Single-seat constituency system strangles macroscopic imagination

Looking back at history, we will find that not all reforms lead to progress or correctness; many times, the outcome of reform is worse — a harmful change. The reform of Japan’s electoral system in the 1990s serves as a typical example of such a harmful change.

Japan used to carry out the multi-seat constituency system that could elect multiple representatives. With competition in elections not very fierce, there was ample room for opposition parties to survive. This led to an incredibly stable “man-based” political landscape. In 1993, a group of young politicians from the Liberal Democratic Party, led by Ichiro Ozawa, rebelled against the veteran leadership and collaborated with opposition parties to establish a new regime under the leadership of Morihiro Hosokawa. In 1994, leveraging the newfound popularity of their regime, this group, under the guise of political reforms, changed the electoral system from multiple-member constituency to single-seat constituency.

However, the single-seat constituency system has begotten numerous ills. One of them is to make competition very brutal. Each constituency could only elect one representative, and even a slight vote swing could alter a politician’s fate drastically. As a result, all representatives have lost their sense of security and have to go all out to win hearts of voters in their constituencies.

Imagine when politicians are solely preoccupied with their own constituencies, what room remains for the country’s macroscopic imagination?

The single-seat constituency system has made vote seeking the most crucial daily task for politicians, turning frequent public appearances into a virtue. Current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who was the longest-serving foreign minister in Japanese history, used to visit his constituency of Hiroshima every week to seek support. After he became prime minister, his first major task was to relocate the G7 summit to Hiroshima.

Another drawback of the single-seat constituency system is that it has centralized the allocation of political funds at parties, intensifying the influence of party politics. This has not only weakened factions within parties but also prevented representative from demonstrating their personalities, further strangling macroscopic imagination.

4. Single-seat constituency system destructs social correction mechanisms

More critically, over the past two decades, the strengthening of party politics under the single-seat constituency system has not only eroded the rights and individuality within political parties but has also taken toll on opposition parties, the administration, media, academia, and other domains.

Under the single-seat constituency system, the popularity of parties largely determines their success. Election somewhat resembles the “Five in a Row” game, where it’s either an all-win or all-lose outcome. The post-election political landscape often becomes one-sided, with the power of opposition parties dwindling and their ability to balance political power diminishing.

In the past, to ensure the neutrality and independence of the administration, political intervene in the appointment and removal of administrative officials is forbidden. However, today, we all know that appointments of high-ranking administrative officials are determined by the prime minister’s office. Political interference in administrative appointments has severely undercut the independence of the entire administrative sphere.

The erosion of power has also become overtly visible in the media. For instance, today, the government’s political motives behind appointing president of NHK, Japan’s national public broadcasting organization, are apparent. The critical power of Japan’s media toward politics is far from what it was 30 years ago.

Academia is not exempt either. On Nov. 21, 2020, during an academic symposium commemorating the 120th anniversary of Tokyo Keizai University, I invited Professor Takashi Onishi, former president of the Japan Academy Council, and Tokuo Nakai, vice minister of environment, to weigh in with their views in a dialogue. During the conversation, Onishi expressed strong dissatisfaction with the interference of higher authorities in academic appointments. Not too long ago, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, without providing any specific reasons, rejected the appointment of six members nominated by the Japan Academy Council, triggering a strong backlash from the academic community.

The spillover of political erosion hasn’t just killed macroscopic imagination but has also severely damaged Japan’s social correction mechanisms. This is also why consecutive increases in the consumption tax rate under the Abe administration did not evoke the same kind of backlash threatening the stability of the regime as before.

The article was first published on China Daily, China.org.cn on Sep. 13, 2023 and reprinted by other news websites.