Cloud River Urban Research Institute

Editor’s note:

Chinese cities still face environmental challenges although their increasing wealth. Which Chinese megalopolis enjoys best climate conditions? Which Chinese megalopolis has the highest agricultural productivity? Which megalopolis boasts the best air quality? And which megalopolis faces the most daunting task in reducing carbon emissions? In the environmental rankings of the China Integrated City Index 2022, Cloud River Urban Research Institute has utilized a series of environmental data to analyze the environmental quality and challenges of 19 megalopolises in China.

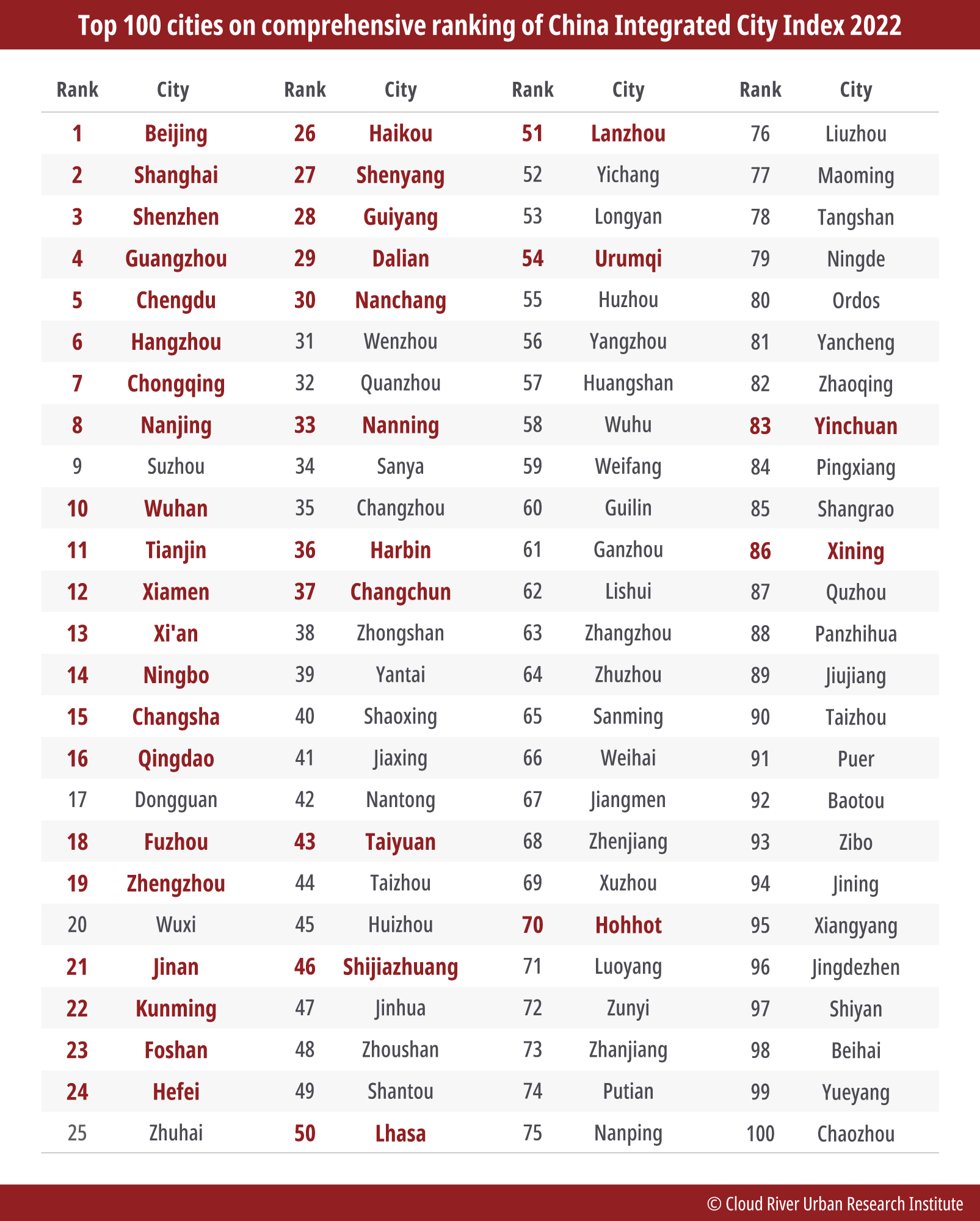

1. Large cities dominate environmental rankings

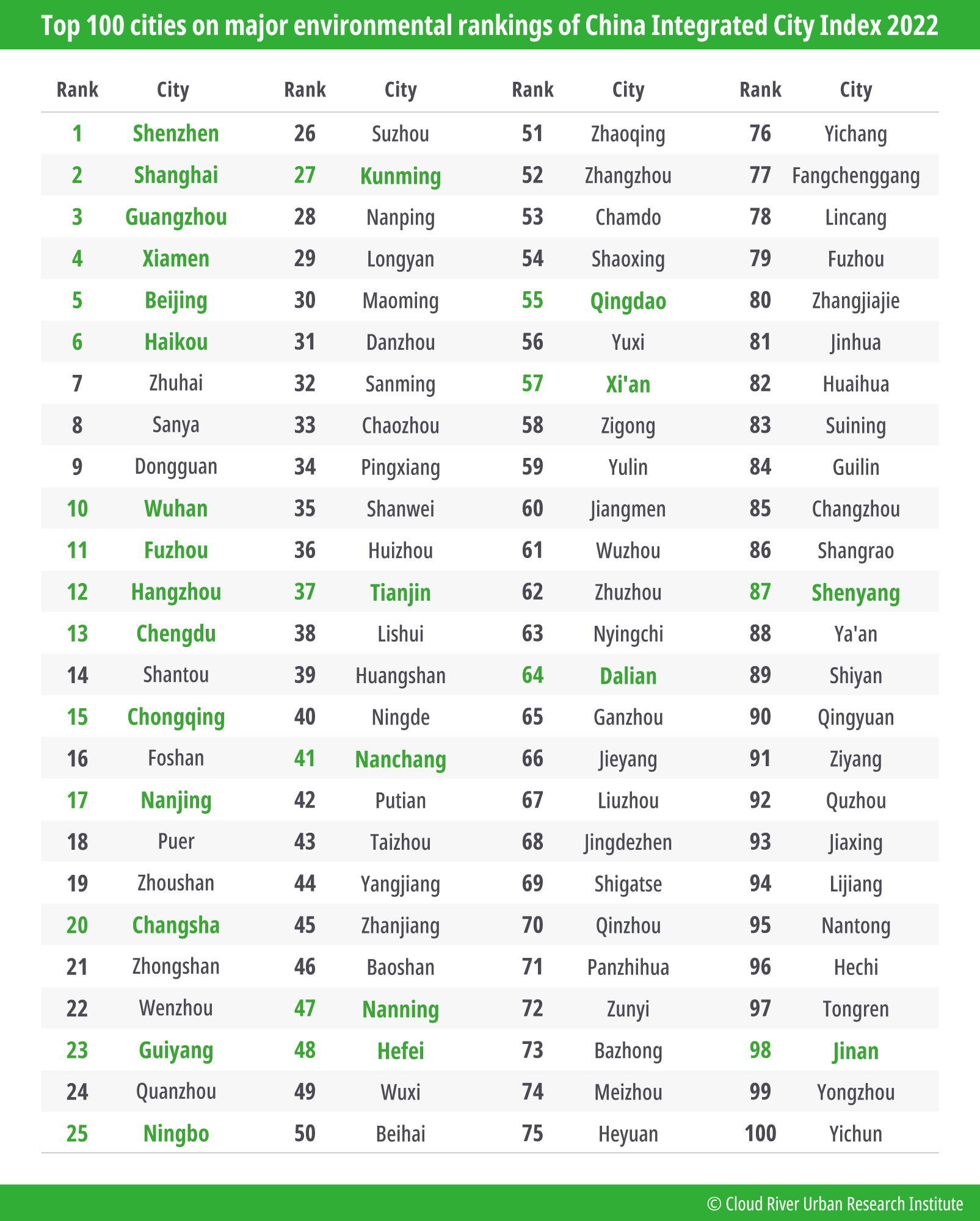

According to the major environmental rankings of the China Integrated City Index 2022 (hereinafter referred to as the Index), the top 10 cities are Shenzhen, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Xiamen, Beijing, Haikou, Zhuhai, Sanya, Dongguan, and Wuhan. Compared to 2021 rankings, economically developed cities have made into the top 10. This is because the 2022 edition puts more emphasis on investment in environmental improvement compared to the 2021 edition.

Huang Weibo, a former senior official of the National Development and Reform Commission, commented, “The environmental rankings of the Index reveal that the top 10 cities, excluding Wuhan, are all located in eastern China. This shows the region’s efforts toward green development. As a national core city, Wuhan has played a leading role in promoting high-quality development in central China in the new era.”

Ming Xiaodong, former first-level inspector of the Department of Development Planning of the National Development and Reform Commission and former minister-counsellor of the Chinese Embassy in Japan, pointed out the environmental rankings of the Index encompasses natural ecology, environmental quality, and spatial structure, includes nine sub-items, namely soil and water endowment, climate conditions, natural disasters, pollution load, environmental efforts, resource efficiency, compact urban areas, transportation networks, and urban facilities, utilizes 452 sets of environmental-related data, and ranks 297 cities at or above the prefectural level and 19 megalopolises.

He said the results show that economically developed cities and rapidly developing megalopolises have achieved significant success in high-quality development. The top 20 cities include four first-tier cities, six quasi-first-tier cities, and nine second-tier cities.

He said these cities have their own characteristics, including the most economically developed, those that have experienced rapid development in recent years, and those continuously optimizing their industrial structures. This indicates that improving the ecological environment and achieving China’s dual carbon goals entail not only arduous efforts but also solid economic and technological support.

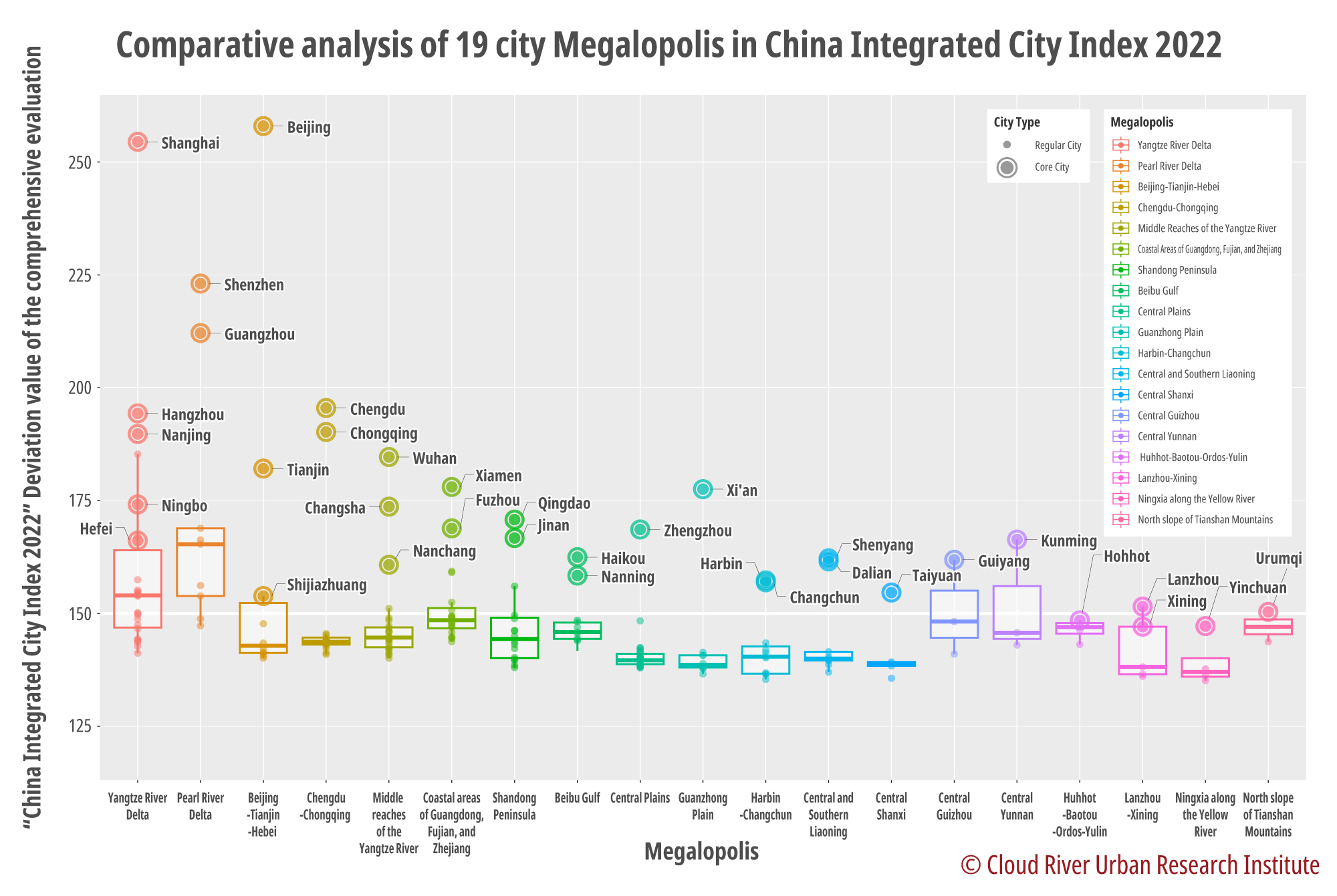

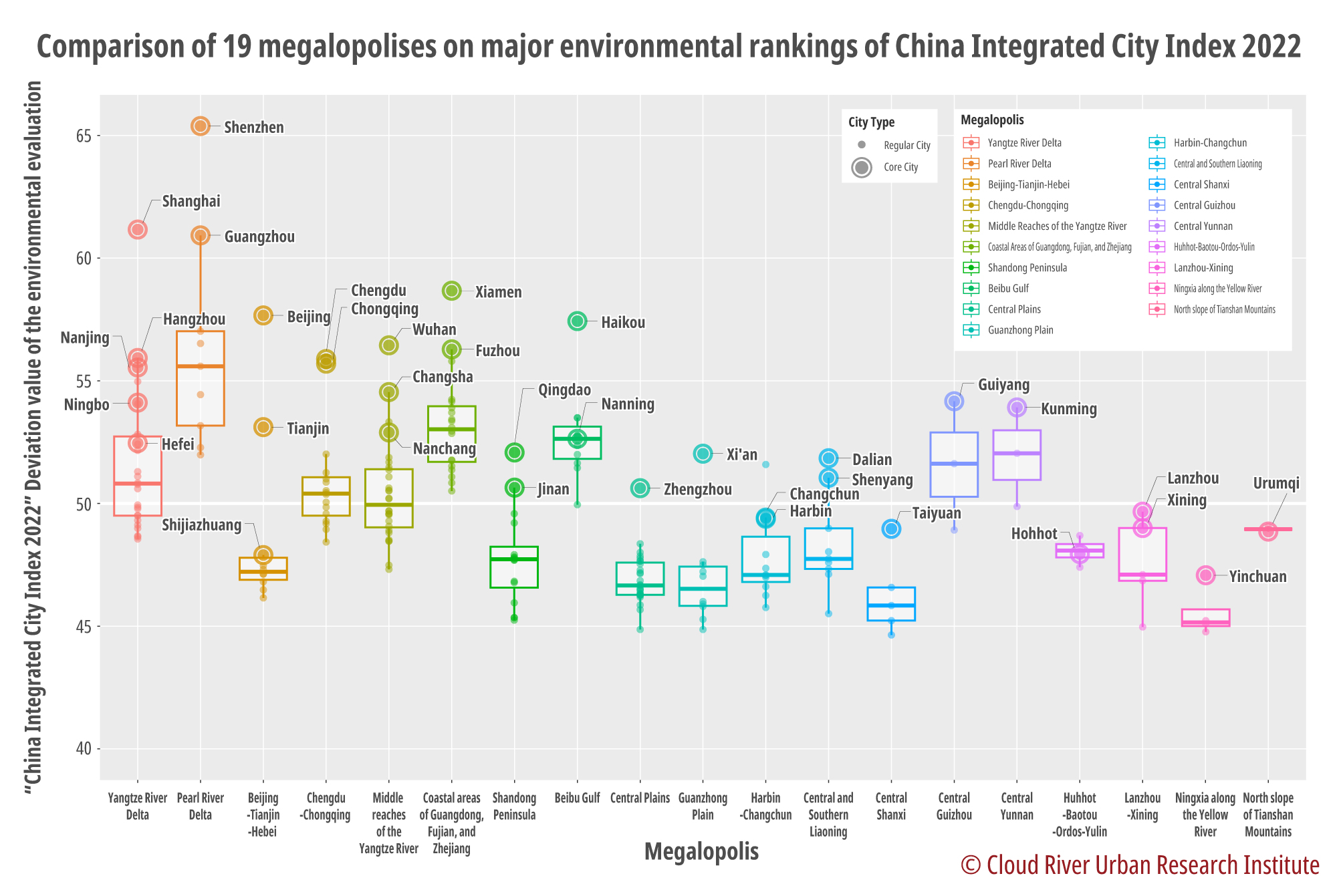

This article focuses on analyzing the performance of the 19 megalopolises in terms of environment in 2022. Using box plots and overlaid bee swarm plots, the article presents the distribution and degree of deviation in the environmental rankings of 223 cities at or above the prefectural level in the 19 megalopolises. The Pearl River Delta fares best, followed by coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang provinces, the Beibu Gulf, central Yunnan, central Guizhou, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle. The remaining 12 megalopolises have their environmental indicators below the national average, with the areas along the Yellow River in northern Ningxia ranked at the bottom.

Ming Xiaodong noted that among the seven megalopolises with environmental indicators above the national average, there are two first-tier megalopolises, two quasi-first-tier megalopolises, and three second-tier megalopolises. Among the 12 megalopolises with their environmental indicators below the national average, there is one first-tier megalopolis, two quasi-first-tier megalopolises, seven second-tier megalopolises, and two third-tier megalopolises. The megalopolises near the top on the rankings mostly have large GDP and favorable natural conditions.

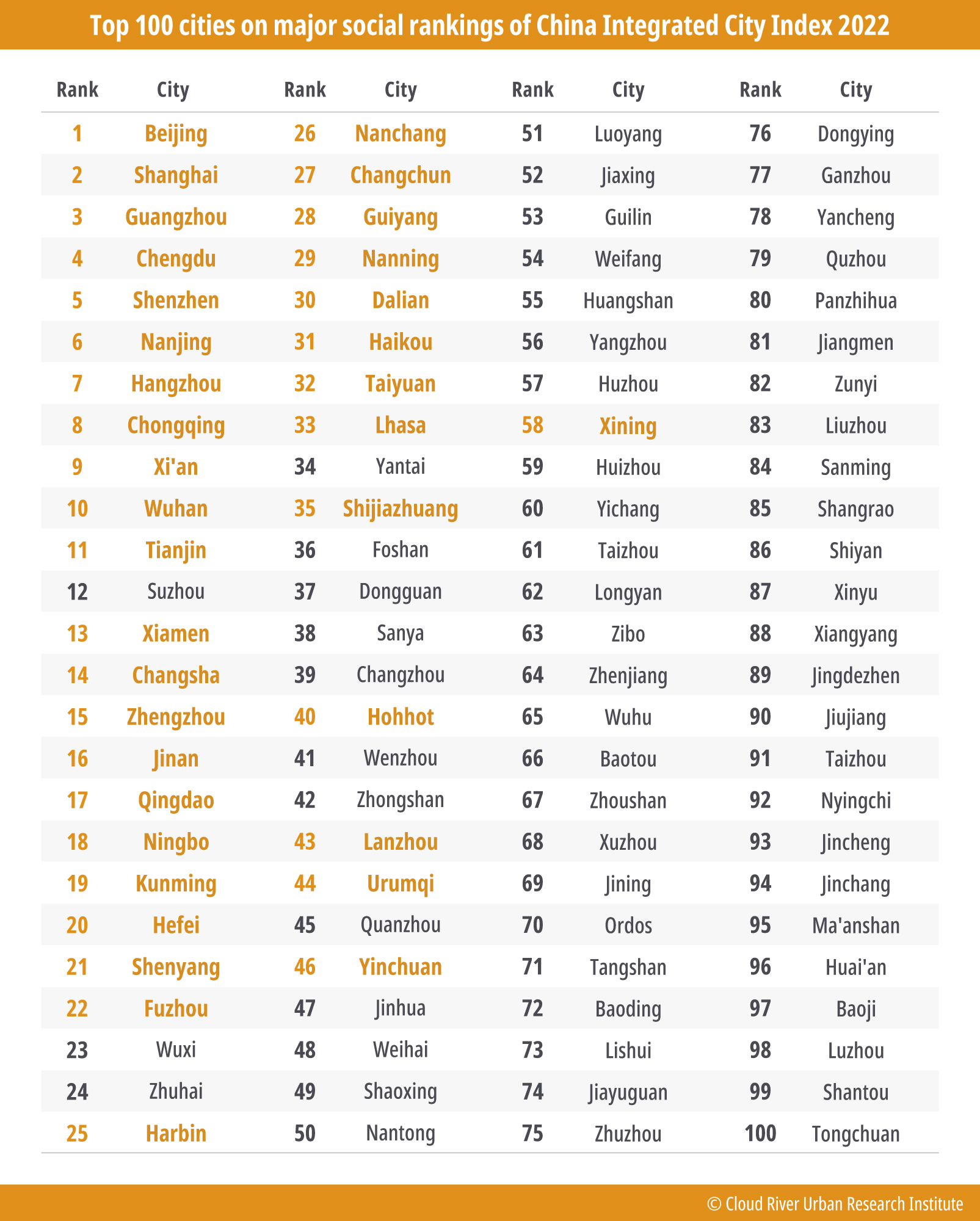

Top 100 cities on major environmental rankings of China Integrated City Index 2022

2. Comfortable climate key to population concentration

Climate is one of the most crucial factors for human habitation. Among the 19 megalopolises, the ones with the best climate are the Pearl River Delta, the Beibu Gulf, central Yunnan, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang provinces, the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, central Guizhou, and the Yangtze River Delta. These megalopolises are predominantly located in southern China. Approximately 45.5% of China’s population concentrates in these megalopolises which enjoy a good climate.

The climate comfort of the remaining 11 megalopolises is below the national average, among which the Harbin-Changchun region and the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains are endowed with the least favorable climate conditions.

3. Most first-tier and quasi-first-tier cities concentrate in areas with higher rainfall

Rainfall is another crucial factor for human habitation. Among the 19 megalopolises, those with the highest rainfall are the Pearl River Delta, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang provinces, and the Beibu Gulf. Other city clusters with above-average rainfall include the Yangtze River Delta, the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, and central Guizhou. Three out of four first-tier cities and seven out of nine quasi-first-tier cities are concentrated in areas with rainfall above the national average. These seven megalopolises are located in southern China.

The remaining 12 megalopolises have their rainfall levels below the national average, with the areas along the Yellow River in northern Ningxia and the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains having the least rainfall, followed by the Hohhot-Baotou-Erdos-Yulin region, and the Lanzhou-Xining region.

4. Agricultural productivity varies from north to south

Agricultural productivity is higher in southern China and lower in northern China. Among the 19 megalopolises, the areas with the largest arable land are the Harbin-Changchun region and the Central Plains, accounting for 11.2% and 10.7% of the national total, respectively. Among the first-tier megalopolises, the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region account for 4.5%, 0.4%, and 3.1% of the national total, with the Pearl River Delta taking the smallest share. Among quasi-first-tier megalopolises, the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang provinces, and the Guanzhong Plain account for 4.8%, 6.6%, 2.1%, and 2.4% of the national total, with the middle reaches of the Yangtze River taking the largest share.

The Pearl River Delta, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang provinces, the Beibu Gulf, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle have highest agricultural productivity (GDP of the primary industry per unit of arable land), all above the national average. Agricultural productivity of the remaining 14 megalopolises is below the national average, among which Harbin-Changchun region and the Central Plains have the largest arable land.

Professor Zhou Muzhi, head of Cloud River Urban Research Institute, pointed out agricultural productivity is influenced by not only natural factors such as climate, land resources, and water resources, but also investment in agriculture. It can be seen that the five megalopolises with agricultural productivity above the national average are all in southern China, and most of them have strong capabilities for substantial investment in agriculture.

5. Northern China faces bigger carbon reduction challenges than southern China

As the dual carbon goals become China’s national strategy, carbon emissions serve as a significant indicator for assessing low-carbon economic development in different regions. The Yangtze River Delta takes the largest share of China’s carbon emissions with 16%. The Pearl River Delta and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region take 5.6% and 8.6%, respectively. The three regions contribute a combined 30.2%. Among quasi-first-tier megalopolises, the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang provinces, and the Guanzhong Plain take shares of 2.9%, 4.7%, 4.7%, and 3.1%, respectively, totaling 15.4%. Additionally, the Central Plains, the Shandong Peninsula, the Harbin-Changchun region, the Hohhot-Baotou-Erdos-Yulin region, and central and southern parts of Liaoning take 8.8%, 7.8%, 4.9%, 3.3%, and 2.9% of carbon emissions, respectively. The total carbon emissions from the 19 megalopolises account for 80.9% of the national total.

Ming Xiaodong pointed out that megalopolises are densely populated areas and large carbon emitters. They are key to achieving the dual carbon goals and the goal of building a beautiful China. The carbon emissions of the three first-tier and four quasi first-tier megalopolises account for 45.6% of China’s carbon emissions.

He said, “These megalopolises make significant efforts in carbon reduction, and we anticipate continuous improvement in the quality of the development of cities in the megalopolises.”

Carbon intensity, also known as carbon emissions per unit of GDP, is an important indicator for measuring the relationship between the economy and carbon emissions. Among the 19 megalopolises, the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle has the best showing in terms of carbon intensity, followed by the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, central Guizhou, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang provinces, the Beibu Gulf, the Pearl River Delta, and the Yangtze River Delta. These seven megalopolises all exceed the national average and are located in southern China.

Carbon intensity of the remaining 12 megalopolises stays below the national average. Among them, the Harbin-Changchun region has the lowest carbon intensity, followed by the areas along the Yellow River in northern Ningxia, the Hohhot-Baotou-Erdos-Yulin region, the central part of Shanxi, the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains, the central and southern parts of Liaoning, the Guanzhong Plain, and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. These eight megalopolises are all in northern China.

Zhou Muzhi pointed out, “Compared to 2000, carbon intensity in China was reduced over 40%, marking a significant achievement. However, there is still a considerable gap China and developed countries. Currently, China’s carbon intensity is 2.8 times that of the U.S. and Japan, 3.6 times that of Germany, 5.5 times that of the U.K., and 6 times that of France. Therefore, achieving a low-carbon development model is a daunting task for every Chinese city.”

6. Northern China still face dire challenges from air pollution

Air quality is one of the most important gauges of environmental quality in a region. Central Yunnan, central Guizhou, the Pearl River Delta, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang provinces, and the Beibu Gulf take top spots on the Air Quality Index (AQI), with their indicators all above the national average.

Megalopolises at 7th to 20th places are all below the national average, with the Central Plains logging the poorest air quality, followed by the areas along the Yellow River in northern Ningxia, central Shanxi, the Shandong Peninsula, the Lanzhou-Xining region, the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains, and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Moreover, these seven regions are all located in northern China. Although China’s air quality has improved significantly in recent years, pressures remains severe in northern China.

7. Green designs concentrate in first-tier and quasi-first-tier megalopolises

Green building designs embody environmental awareness and the endeavor toward environmental protection. The evaluation marks for green building designs are most concentrated in the three first-tier megalopolises — the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region — accounting for 39.1%, 15%, and 17.9% of the national total, respectively. The combined share of these three regions is 72%. Among the quasi-first-tier megalopolises, the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, coastal areas of Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang provinces, and the Guanzhong Plains are home to 4.7%, 4.1%, 4.7%, and 1.1% of the national total, respectively, 14.6% in total.

Huang Weibo pointed out, “In terms of green building designs, the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region contribute 72% to the national total. The figure reflects the active promotion of green industry development in these regions as part of the implementation of major national strategies, as well as their contribution to achieving dual carbon goals.”

Yang Weimin, former deputy director of the Office of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Affairs of China, summarized, “China’s modernization has multiple goals, including achieving sustained economic growth, fundamental improvement in eco-environment, common prosperity for all, national security and social stability, and peak carbon and carbon neutrality.

He said the Index provides a comprehensive diagnosis of the environment in Chinese cities and megalopolises, and offers an important perspective on observing the environmental conditions during the modernization process. It is evident that an evaluation from an environmental perspective is not the same as from an economic perspective; some indicators are determined by natural conditions, while others are related to how much effort put. Cities and megalopolises need to coordinate multiple goals. That means they should develop their economy while paying attention to the environment.

Compare 19 megalopolises on major environmental rankings of China Integrated City Index 2022

The article was first published on China SCIO, China.org.cn on Jan. 12, 2024 and reprinted by other news websites.